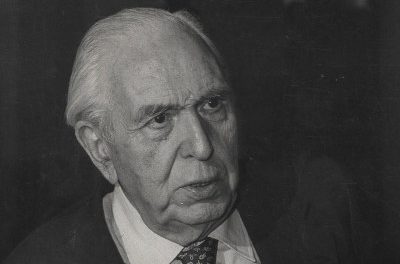

Francisco González Redondo

Francisco González Redondo, Professor of History of Science at the Faculty of Education of the Complutense University of Madrid and collaborator of the Royal European Academy of Doctors (READ), took part in the Biennial Congress of the Royal Spanish Mathematical Society, held at the University of Alicante from January 19 to 23, with the presentation “At the Origins: Art and Mathematics in Prehistory”, which he organized and curated. The project includes an exhibition of the same title that he has presented over the past year at various venues throughout Spain and which reached its culmination at this scientific meeting. González Redondo had previously explored this same field with the exhibition “Art, Mathematics and Gender in Prehistory”, one of the main attractions of the 13th Madrid es Ciencia Fair, accompanied by the lecture “Were the ‘First Mathematicians’ Women?”.

Through a linear tour of ten panels featuring QR codes that link to audio recordings of all texts in English, French, German, and Spanish, as well as videos in sign language, visitors were able to discover the intrinsic relationship between various forms of prehistoric rock art and a symbolic language with a mathematical basis. “Prehistoric figurative art may have had an aesthetic purpose, but abstract claviform and scalariform signs and collections of dots can hardly be considered works of art, and their meaning should be interpreted from another perspective—that of mathematics,” the exhibition noted. In this regard, the expert points out that there are numerous abstract symbolic prehistoric manifestations that contain a type of non-figurative record interpretable from a mathematical perspective and which may represent accounting annotations or even astronomical calendar records.

Rock art, by PxHere

“In the Upper Paleolithic, our ancestors already demonstrated the capacity to symbolically record thought. However, alongside horses, deer, goats, or bison painted on cave walls or engraved on bone, Prehistory also offers abstract symbolic manifestations containing a non-figurative type of record that apparently can only be understood from a mathematical perspective. In fact, the interpretation of this symbolic record as accounting annotations and even calendar-astronomical records is increasingly being accepted. This exhibition presents a transdisciplinary analysis of the most distinctive archaeological findings with plausible mathematical content and puts forward a hypothesis: were their authors primarily women?” explains the exhibition’s curator.

González Redondo revisits the work of various anthropologists, mathematicians, and historians of science such as Dana Taylor, who argues that the cyclical nature of menstruation played an essential role in the development of accounting, mathematics, and the measurement of time; Claudia Zaslavsky, who maintains the thesis that women were the first mathematicians in history; Marylène Patou-Mathis, author of “Prehistoric Man Is Also a Woman”; and Marga Sánchez Romero, who in her book “Prehistory of Women” defends similar arguments. Together, these perspectives support the hypothesis that places women at the center of these symbolic representations of Prehistory.

In any case, the expert emphasized the exhibition’s strong educational and exploratory character. “It is an exhibition accessible to all audiences. The aim is to awaken curiosity and encourage people, once they leave the exhibition, to go home and continue studying and asking questions. This is what we scientists and teachers must do: awaken curiosity and provoke questions, rather than deliver dogmatic lessons about issues for which there is no single answer,” González Redondo concluded.